Mackinder’s Heartland Theory

Divide et impera (divide and conquer) is the modus operandi for any imperial system—and emphatically that of the British Empire. The British instigated tensions in Ukraine are part of this “divide and conquer” strategy, and have very little to do with that nation, and entirely to do with where it lies on the map of British geopolitical considerations. If China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) continues to expand, and if the BRI continues to integrate with the Russia initiated Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) as Presidents Xi and Putin recently discussed on sidelines of the Olympics in Beijing, then the British Empire is finished. The 2014 coup d’état in Ukraine was to prevent any orientation of Ukraine to the emerging BRI-EEU collaboration and was designed to force Ukraine into the European Union on its way to NATO membership—forcing the present red-line of Russia. Moreover, had Ukraine integrated into the broader development of the Belt and Road Initiative, then the door to western Europe would also have opened to the expanding BRI. This is the context for the present policies of NATO against Russia and China as a revival of the fault lines of the Cold War.

The first Secretary General of NATO, Lord Ismay, said that the purpose of NATO was “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Ismay was the personal secretary of Winston Churchill and dutifully carried out Churchill’s design for lowering the “iron curtain” to separate those nations who had just defeated the Nazi scourge, which was of course supported by the British monarchy as a weapon against Russia, and Eurasia in general. However, both the design of NATO and the support of fascism in Europe to be used for the control of Eurasia, has its roots in the British strategy in central Asia (centered on Afghanistan) called the “Great Game,” as well as the geopolitical thinking of Halford Mackinder, author of The Geographical Pivot of History (1904).

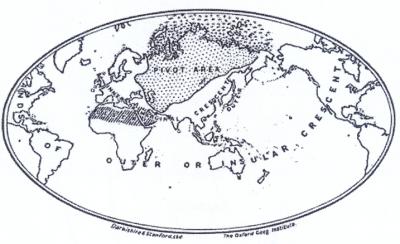

Map of Mackinder’s heartland concept. China’s BRI would have been Mackinder’s worst nightmare.

Mackinder’s “Heartland Theory” lamented the growing expansion of the American System in Europe—especially in Germany— and Asia during the 19th century and early 20th century. The emergence of the “Baghdad to Berlin Railway,” the Russian “Trans-Siberian Railway,” and the potential to connect that through Manchuria to Sun Yat Sen’s designs for railways in China, would have sounded the death knell for the British and their maritime empire. Mackinder used the image of the railways as the new version of the Mongol Hordes coming to conquer Europe to instill a sense of fear in his fellow British imperialists.

The Russian railways have a clear run of 6000 miles from Wirballen in the west to Vladivostok in the east. The Russian army in Manchuria is as significant evidence of mobile land-power as the British army in South Africa was of sea-power. True, that the Trans-Siberian railway is still a single and precarious line of communication, but the century will not be old before all Asia is covered with railways. The spaces within the Russian Empire and Mongolia are so vast, and their potentialities in population, wheat, cotton, fuel, and metals so incalculably great, that it is inevitable that a vast economic world more or less apart, will there develop inaccessible to oceanic commerce.

As we consider this rapid review of the broader currents of history, does not a certain persistence of geographical relationship become evident? Is not the pivot region of the world’s politics that vast area of Euro-Asia which is inaccessible to ships, but in antiquity lay open to the horse-riding nomads, and is today about to be covered with a network of railways?